THE ULTIMATE GUIDE TO BRAZILIAN CINEMA

words by LEANDRO DA SILVA

Brazilian cinema has been making its presence felt at major international festivals for decades. Beyond aesthetics, these films carry cultural impact, political nuance, and emotional depth that resonate far beyond national borders. But every industry has its defining moments — and Brazil has several.

One of the most iconic milestones was Central Station (1998), directed by Walter Salles. In 1999, the film received two Academy Award nominations: Best Actress for Fernanda Montenegro and Best Foreign Language Film. That same year, it competed at the Golden Globes, winning Best Foreign Language Film. Fernanda Montenegro was also nominated for Best Actress in a Motion Picture – Drama, solidifying her status as one of Brazil’s greatest performers on the international stage.

But time has its own dramaturgy, and sometimes life really does imitate art. It’s not just legacy — it’s continuity.

Twenty-six years later, another Fernanda stood in the same spotlight. Fernanda Torres, daughter of Fernanda Montenegro, received her first Golden Globe nomination — and won — in the same category, Best Actress in a Motion Picture – Drama, for I’m Still Here (2024), once again directed by Walter Salles. Montenegro appears in the film.

images via imdb.com

Two Fernandas. Mother and daughter. Same award. Same category. Same director. Twenty-six years apart. They don’t just make films — they create cinematic narrative in real life. So here’s the question: does this story deserve to become their next movie? The audience is certainly rooting for it.

More recently, excitement rose again with The Secret Agent (2025), directed by Kleber Mendonça Filho and starring Wagner Moura, chosen to represent Brazil in the Oscar race. Expectations for Brazilian cinema have never been higher.

In this special selection, we dive into films that shaped history and new releases you can’t miss. These are works that will expand your worldview, challenge narratives, and above all, show that cinema made in Brazil is powerful, diverse, and transformative. Get ready: watching these films may change the way you see cinema.

BACURAU (2019)

directed by KLEBER MENDONÇA FILHO & JULIANO DORNELLES

image via imdb.com

Bacurau takes place in a remote village in the Brazilian backlands that mysteriously disappears from digital maps. When outsiders begin to arrive under suspicious circumstances, the community realises the isolation is not accidental — it’s part of a violent plan. What follows is a collective act of resistance, where survival depends on unity, memory, and identity.

Bacurau is one of those films where you have no idea what’s coming. At first, you’re immersed in the rhythm of everyday life in that community — it feels like you're being transported into their routine — and then suddenly, everything shifts.

Winner of the Jury Prize at the 2019 Cannes Film Festival, the film also swept the Brazilian Film Academy Awards and won Best International Film at the Munich Film Festival. Blending thriller, western, and political allegory, Bacurau is gritty and unapologetic. It transforms a remote community into a symbol of defiance. Bacurau is more than a story of attack — it’s the portrait of a Brazil that refuses to be erased.

MANAS (2024)

directed by MARIANNA BRENNAND

image via imdb.com

Manas, directed by Marianna Brennand, is the kind of film that stays with you long after the final frame. It tells a story of violence through silence — and of the courage required to break it. Although rooted in the remote island of Marajó, in northern Brazil, its truth is painfully universal. Around the world, women are expected to endure abuse simply for existing in a patriarchal, misogynistic society: emotional, sexual, moral, psychological, physical, financial. In different ways, we have all witnessed or lived it. Originally, Brennand intended to make a documentary. But she realised that asking real survivors to revisit their trauma would reopen wounds that had never healed. Fiction became her act of protection — and Manas became her first narrative feature.

Thirteen-year-old Marcielle (Tielle) lives with her family along the Amazon River. Her childhood should be defined by river play, collecting açaí, and watching telenovelas with friends. Yet adolescence arrives too early in Marajó. Girls are taught not to hope for education or independence, but for “a good man” — a ticket out of poverty and into a different kind of captivity. As Tielle’s world fractures, she begins to understand the oppressive cycle that traps the women around her. She fears for her younger sister. She discovers a strength she never knew she had. Brennand directs with restraint, not spectacle. We don’t watch violence — we feel its consequences.

Winner of the Directors Award at Venice (Giornate degli Autori) and the International Newcomer Award at the Mannheim–Heidelberg International Film Festival, Manas is already positioning Brennand as one of the most relevant new voices in Brazilian cinema. Manas looks directly at violence — and refuses to let it remain invisible. This film stays with you not for what it shows, but for what it refuses to ignore.

LATIN BLOOD — THE BALLAD OF NEY (2025)

directed by ESMIR FILHO

image via imdb.com

Latin Blood — The Ballad of Ney (Homem com H), directed by Esmir Filho, revisits significant moments in the life and career of Ney Matogrosso — a Brazilian icon whose presence transformed music, performance, and the very idea of artistic freedom. The film follows his childhood in a military environment, the explosive rise of Secos & Molhados in the 1970s, and the consolidation of his solo career, which turned Ney into a symbol of expression and liberation. Blending a sensorial approach with performance and visual experimentation, the film does not try to list facts — it tries to capture essence.

Making a film about Ney Matogrosso means facing a unique challenge: Ney is not only a monumental Brazilian artist, he is a force of transformation. Throughout his career, he reinvented himself — musically, visually, politically — and his presence on stage became a powerful statement of freedom. For many Brazilians, Ney represents the moment when art stopped asking for permission.

Jesuíta Barbosa carries the film. He doesn’t imitate Ney — he channels him. The physicality, the way he holds the gaze, the relationship with performance — everything reveals an extraordinary ability to access Ney’s essence without mimicry. Latin Blood raises a larger reflection: perhaps the traditional biopic format is not the best way to portray artists as complex as Ney Matogrosso. His life does not fit into a straight line. Ney exists in movement — in transformation. And the film embraces that.

The result is a film that is less about documenting a life and more about experiencing a presence. Ney Matogrosso has always resisted labels. This film does the most respectful thing possible: it doesn’t try to define him — it tries to feel him.

THE BLUE TRAIL (2025)

directed by GABRIEL MASCARO

image via imdb.com

In The Blue Trail, Brazilian filmmaker Gabriel Mascaro imagines a near-future Brazil where age becomes a form of political control. Tereza, a 77-year-old woman, receives a government mandate: she must relocate to a “senior colony,” where elderly citizens are concentrated so their homes and land can be reassigned to younger generations. Instead of accepting this imposed future, Tereza escapes in the middle of the night and begins a clandestine journey through the Amazon.

Her path is emotional, fragmented, instinctive. Mascaro blends dystopia and road-movie aesthetics, turning the rainforest into a landscape of refuge and rebellion. The film doesn’t dramatize aging as frailty — it frames autonomy as an act of resistance.

Winner of the Silver Bear — Grand Jury Prize at the Berlin International Film Festival (Berlinale) and Best Ibero-American Fiction Film at the Guadalajara International Film Festival, The Blue Trail confirms Mascaro as one of the most inventive and necessary voices in contemporary Brazilian cinema. With striking imagery and emotional restraint, The Blue Trail becomes a story about autonomy, dignity, and the right to exist on one’s own terms. A film about a woman who refuses to surrender her future — even when the world insists on writing it for her.

DOG’S WILL (2000)

directed by GUEL ARRAES

image via imdb.com

Based on Ariano Suassuna’s classic play, A Dog’s Will (O Auto da Compadecida) blends comedy, adventure, and Brazilian folklore into one of the most beloved films in the country’s cinematic history. The story follows João Grilo and Chicó — two clever, penniless men from the arid backlands of Northeast Brazil — who navigate hunger, injustice, and the absurdity of daily life armed only with wit and improvised schemes. As chaos escalates, their tricks lead them to confront corrupt authorities, bandits, and eventually the afterlife itself. It remains one of the most iconic and funniest Brazilian films ever made.

Winner of four awards at the Grande Prêmio Cinema Brasil — Best Director, Best Actor, Best Screenplay, and Best Release — and the highest-grossing Brazilian film of 2000, A Dog’s Will became a cultural landmark. Irresistible dialogue, charismatic performances, and a perfect blend of regional identity and universal storytelling have made the film endure across generations. More than a comedy, it is a story about survival, friendship, and the power of compassion — where humour becomes courage.

CITY OF GOD (2002)

directed by FERNANDO MEIRELLES & KÁTIA LUND

image via imdb.com

Set in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro from the late 1960s through the early 1980s, City of God follows the intertwined lives of young residents whose futures are shaped by poverty, violence, and the drug trade. Through the eyes of Rocket — a boy who dreams of becoming a photographer — the film reveals how crime syndicates rise inside the community and how power shifts from petty thieves to ruthless gang leaders.

Meirelles and Lund create a narrative that is both visceral and intimate, weaving real testimonies into a kinetic visual language. The film refuses to glamorise violence; instead, it exposes its brutal logic and the social structures that feed it. Nominated for four Academy Awards, including Best Director and Best Adapted Screenplay. City of God redefined Brazilian cinema on the global stage. With non-professional actors and raw emotional force, it remains a landmark — a film as urgent today as when it was released. City of God doesn’t just depict a place. It reveals a system.

THE SECOND MOTHER (2015)

directed by ANNA MUYLAERT

image via imdb.com

The Second Mother explores class divides and emotional labor through the intimate dynamics of a household in São Paulo. Val, a live-in housekeeper, has spent years raising the son of the wealthy family she works for while remaining physically distant from her own daughter, who stayed in the countryside. When her daughter, Jessica, arrives to apply for university and temporarily stay in the house, the unspoken social boundaries begin to crack.

Jessica questions rules Val has always accepted — where she can walk, what she can touch, what she deserves access to. Her presence destabilises the hierarchy that structures domestic life, forcing everyone in the house to confront what they believe about privilege, affection, and belonging.

Anchored by Regina Casé’s critically acclaimed performance, The Second Mother premiered at Sundance and Berlin, winning multiple awards and becoming a global reference in contemporary Brazilian cinema. A story about motherhood, dignity, and the courage to challenge the roles society assigns us.

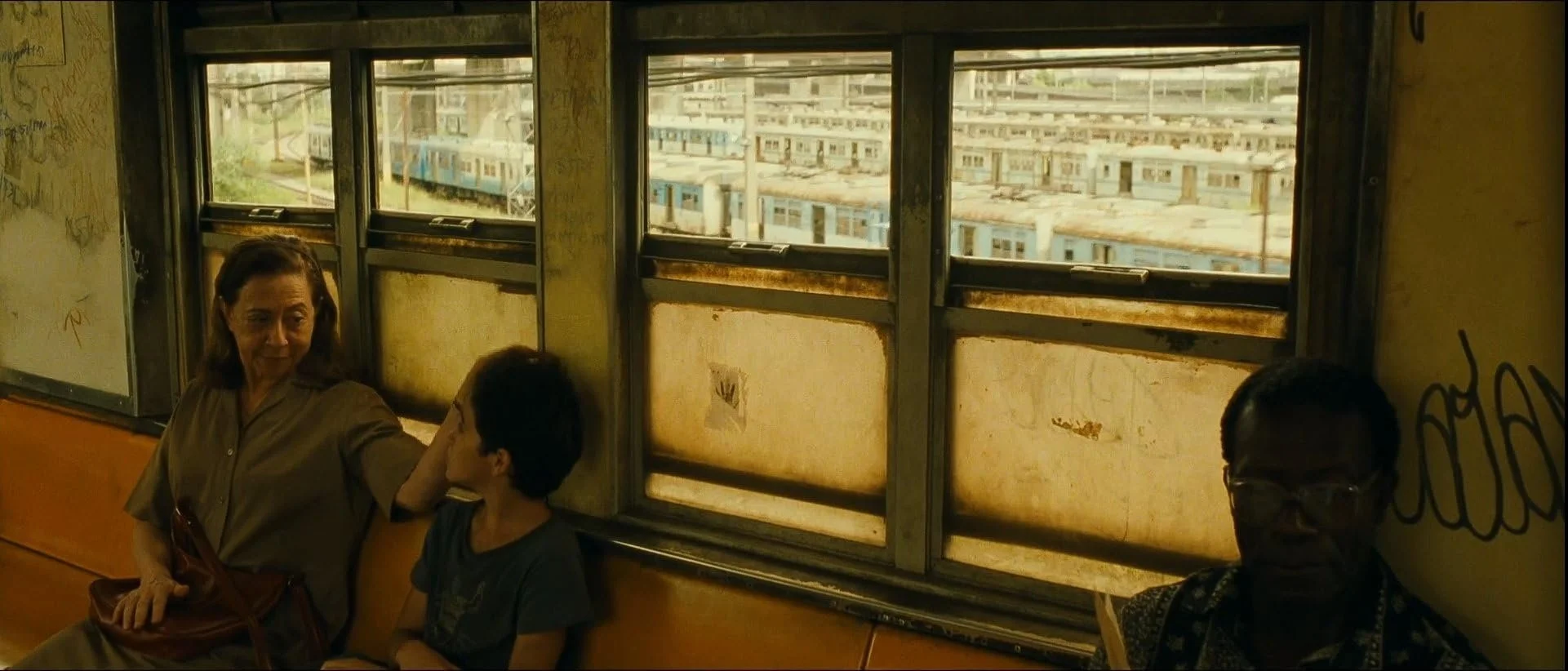

CENTRAL STATION (1998)

directed by WALTER SALLES

image via imdb.com

And here we are with a movie that warms your heart and makes you feel how love can transform a human life. In 1999, Walter Salles’ Central Station reached a historic milestone: it received two Academy Award nominations — Best Actress (Fernanda Montenegro) and Best Foreign Language Film.

In the same year, it competed at the Golden Globes, where it won Best Foreign Language Film. Montenegro was also nominated for Best Actress in a Motion Picture – Drama, cementing her status as one of Brazil’s most celebrated performers worldwide. A turning point that proved Brazilian cinema could shape global narratives.

Central Station tells the story of Dora, a retired schoolteacher who writes letters for illiterate strangers at Rio de Janeiro’s bustling train station. Emotionally detached, she sees her work as routine — until she meets Josué, a young boy whose mother dies unexpectedly. Reluctantly, Dora becomes responsible for him, and together they embark on a journey across Brazil in search of the father he has never met.

As the landscape shifts — from the chaos of urban life to the vast open roads of Brazil’s interior — the emotional distance between them narrows. What begins as obligation becomes a quiet, transformative bond. Both intimate and epic, Central Station is a road movie about unlikely connection — a film that discovers hope in the space between loss and redemption. A story about compassion taking root where it is least expected.

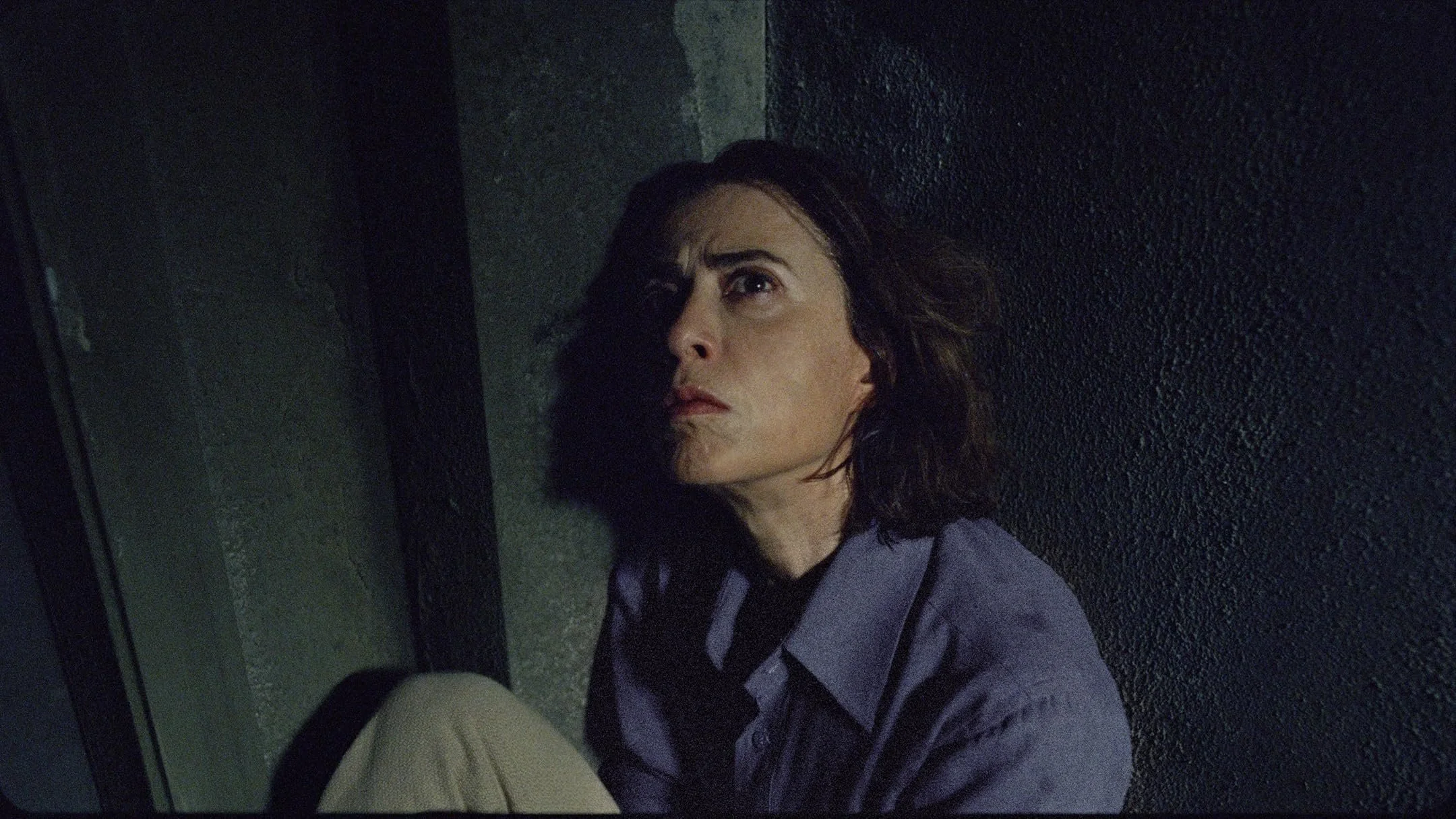

I’M STILL HERE (2024)

directed by WALTER SALLES

image via imdb.com

Winner of the Academy Award (2025) for Best International Feature Film — the first Brazilian film to ever receive this honour. Winner of the Golden Globe (2025) for Best Actress in a Motion Picture – Drama (Fernanda Torres). Nominated at the 97th Academy Awards (2025) for Best Picture and Best Actress (Fernanda Torres). Winner at the Platino Awards (2025) for Best Ibero-American Film, Best Director (Walter Salles) and Best Actress (Fernanda Torres), and nominated for Best Film Not in the English Language at BAFTA 2025.

In I’m Still Here (2024), Walter Salles returns to a filmmaking approach grounded in the intimate and the political. Known internationally for Central Station and The Motorcycle Diaries, Salles has always explored where personal lives collide with history. Here, he turns his focus to Eunice Paiva.

Eunice Paiva was not just a presence during Brazil’s military dictatorship — she was a force against it. A lawyer, a human-rights advocate, and a mother, she spent her life confronting state violence, corruption, and authoritarian power. She fought for truth not only in the courts, but in her home — where the dictatorship left irreversible scars. Fernanda Torres delivers a performance marked by emotional precision and truth. She doesn’t illustrate trauma — she carries it. Her work earned the Golden Globe and multiple international nominations.

Fernanda Montenegro — one of the most respected actresses in world cinema — appears in a pivotal moment that deepens the emotional and political structure of the film. Seeing mother and daughter on screen becomes more than casting: it becomes legacy. Salles directs with clarity and purpose, revealing how political systems infiltrate daily life, how grief becomes activism, and how memory itself becomes resistance. The film looks directly at the present: Brazil still wrestles with the legacy of its dictatorship.

I’m Still Here is intimate and political. A portrait of a woman who refuses to be erased — and proof that insisting on memory is, at times, the most radical act of all.

THE SECRET AGENT (2025)

directed by KLEBER MENDONÇA FILHO

image via imdb.com

Brazil’s official submission for the 2026 Academy Awards — Best International Feature Film. Winner of Best Director, Cannes Film Festival 2025 (Kleber Mendonça Filho), Best Actor, Cannes Film Festival 2025 (Wagner Moura) and FIPRESCI Prize for Best Film, Cannes Competition 2025

Set in Brazil in 1977, during the final years of the military dictatorship, The Secret Agent follows Marcelo, a telecommunications specialist who returns to Recife and becomes entangled in the mechanisms of state control. Rather than relying on spectacle, the film approaches political tension through daily life and the structures that monitor it.

Directed by Kleber Mendonça Filho (Aquarius, Bacurau), the film connects personal events to a wider historical context. Wagner Moura leads the cast, centring the story through a character navigating a country shaped by censorship and surveillance. The Secret Agent positions Brazilian cinema at the centre of the global film conversation — not as a discovery, but as a presence.

This guide is not just a collection of films — it is a treasure chest of stories, memories, and voices that shaped the very identity of Brazilian cinema. I am deeply happy to share these titles with you. Choose a weekend, turn your home into a small cinema, and let these films speak to you. I promise: the journey will be worth it.