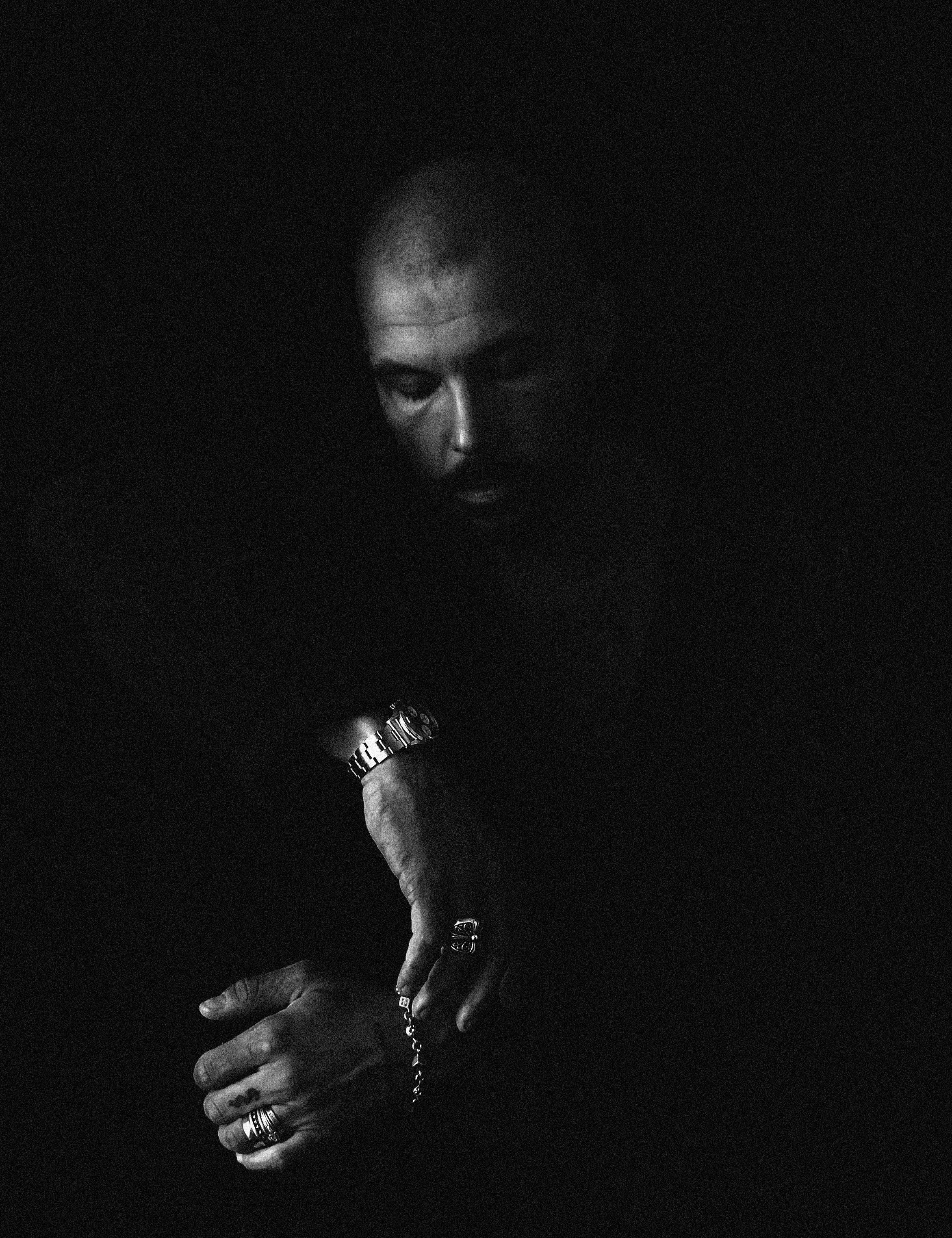

IN CONVERSATION WITH ALEXANDER WESSELY

interview by MAREK BARTEK

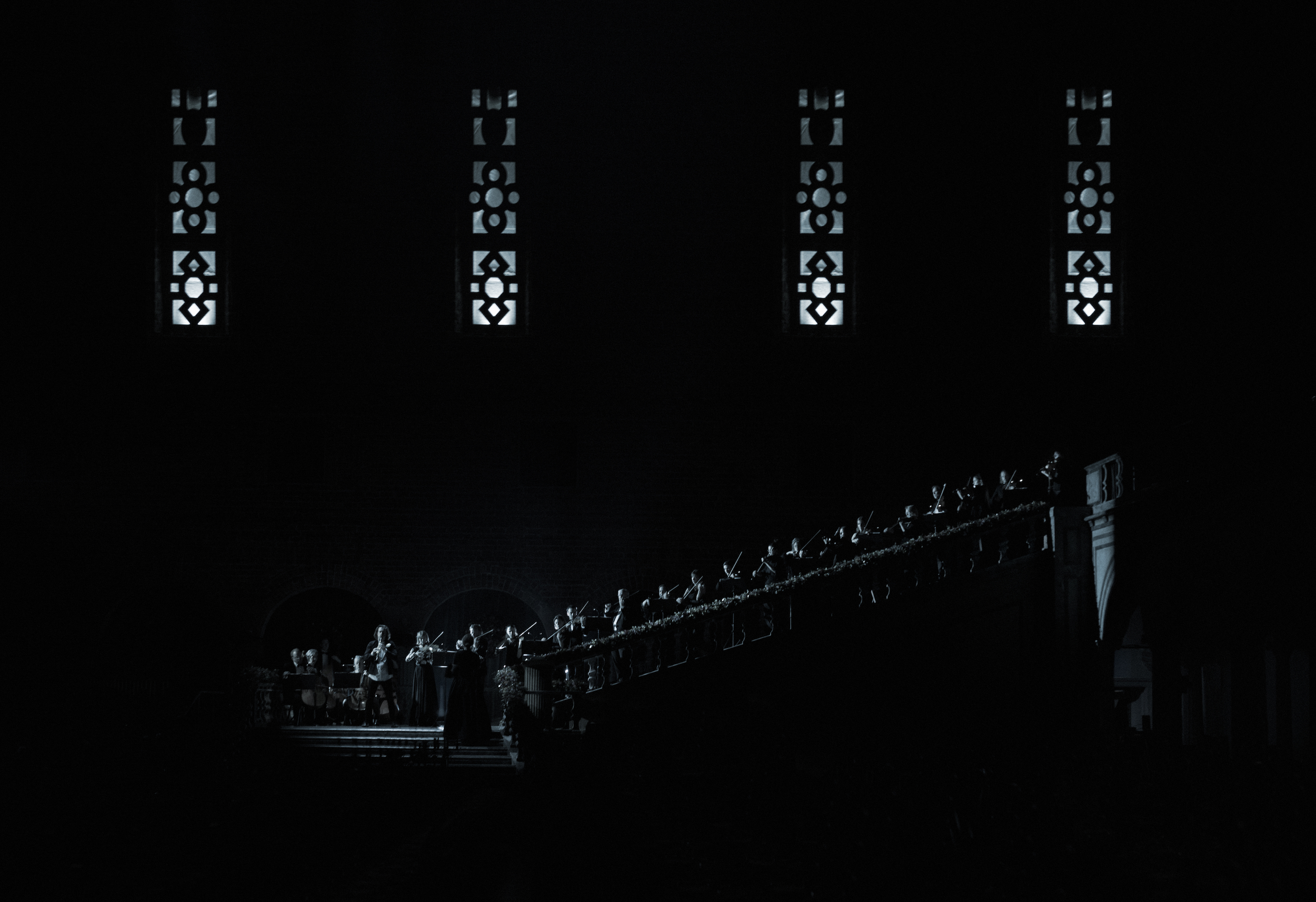

One of the most influential visual artists and creative leaders of his generation, Alexander Wessely, became the first artist commissioned to create living artwork for The Noble Prize ceremony. Together with composer Jacob Muhlrad, Wessely explored the evolution of light from the first spark of dawn.

The Nobel Prize ceremony feels almost untouchable. When you were first invited to reimagine it, what was your starting point? Was there anything that felt non-negotiable to preserve?

My starting point was respect for the ceremony as a structure, not as an image. The architecture, the timing, the collective attention in the room. Those elements felt non-negotiable. I wasn’t interested in adding something on top of the ceremony, but in listening to it and working from within its existing rhythm.

all images courtesy of MOTIF

You chose light as both your material and your metaphor. At what moment did light become the central language of this installation, and what does it allow you to express?

Light has always been central to my work, but here it became unavoidable. In a space defined by history, light is one of the few elements that can transform perception without altering form. It allows me to work with presence, knowledge, and belief without becoming illustrative. Light can suggest meaning without fixing it.

This is the first time the Nobel celebration unfolds as a living artwork. How did you approach shaping a narrative that had to be experienced in real time?

I approached it as a temporal composition rather than a visual sequence. The narrative is carried by pacing, restraint, and progression. It unfolds through attention rather than explanation. Because it exists in real time, the work depends on patience and trust. Nothing happens instantly, and that delay becomes part of the experience.

The installation is structured across three acts — The Dawn, The Monolith, and The Pulse. What was the inspiration for each of them, and how do they work together to share your message?

The Dawn refers to light as a natural and shared condition. The Monolith introduces light as something constructed, symbolic, and designed. The Pulse reflects our present moment, where light becomes rhythm, signal, and data. Together, the acts trace a movement from nature to structure to acceleration, mirroring how humanity relates to knowledge and progress.

How did the Stockholm City Hall’s architecture influence the way light, sound, and movement were choreographed within the space?

The architecture dictated everything. The verticality, the weight of the brick, the processional movement through the hall. Rather than fighting the space, the work follows its logic. Light was treated as something that reveals the architecture slowly, allowing shadows and mass to remain present rather than erased.

To make this art piece come to live, you collaborated with the composer Jacob Muhlrad. How did sound and light evolve together during the creative process?

Sound and light developed in parallel rather than in hierarchy. Jacob’s music carries a strong internal structure, and my role was to listen closely to its timing and density. We avoided direct translation. Instead, light responds to rhythm, silence, and duration, allowing both languages to remain distinct while resonating together

With an audience that includes Nobel Laureates, scientists, artists, and heads of state, there is an inherent weight of expectation. Did that responsibility shape your artistic decisions — or did you consciously try to push against it?

I was aware of the responsibility, but I didn’t let it dictate the work. If anything, it reinforced the need for restraint. In a room filled with authority and achievement, subtlety becomes powerful. I wasn’t interested in impressing the audience, but in creating conditions for presence.

As the ceremony concluded, light reached its most expansive and immersive form. What did you hope lingers with the audience once the hall returns to darkness?

I hope what remains is not an image, but a sensation. A memory of scale, silence, and attention. When the light disappears, the space belongs to the body again. That transition back into darkness is as important as the illumination itself.

Sure enough, right after the ceremony people attending talked to you. What was their immediate reaction to your work, and was it aligned with what you hoped it to be?

People spoke about the atmosphere, time slowing down, and a sense of concentration. That aligned with my intention. The work wasn’t meant to provoke consensus, but to allow individual reflection. In that sense, the responses felt appropriate.