IN CONVERSATION WITH LEO HOLDER & ROBERT GARLAND

interview by JANA LETONJA

IN CONVERSATION WITH LEO HOLDER

As the son of the late, legendary Geoffrey Holder, Leo Holder carries forward an extraordinary creative legacy that bridges dance, design, and cultural imagination. This year, he steps into a pivotal role as artistic supervisor for the Dance Theatre of Harlem’s long-awaited revival of ‘Firebird’, the iconic ballet first choreographed by John Taras and designed by Geoffrey Holder in 1982. With its lush Caribbean-inspired setting, fantastical costumes, and timeless themes of love and liberation, ‘Firebird’ has been reimagined for a new generation while preserving the original’s brilliance and spirit. Under Leo’s careful guidance, the production not only honors his father’s artistry but also reignites DTH’s legacy of innovation, diversity, and storytelling through movement.

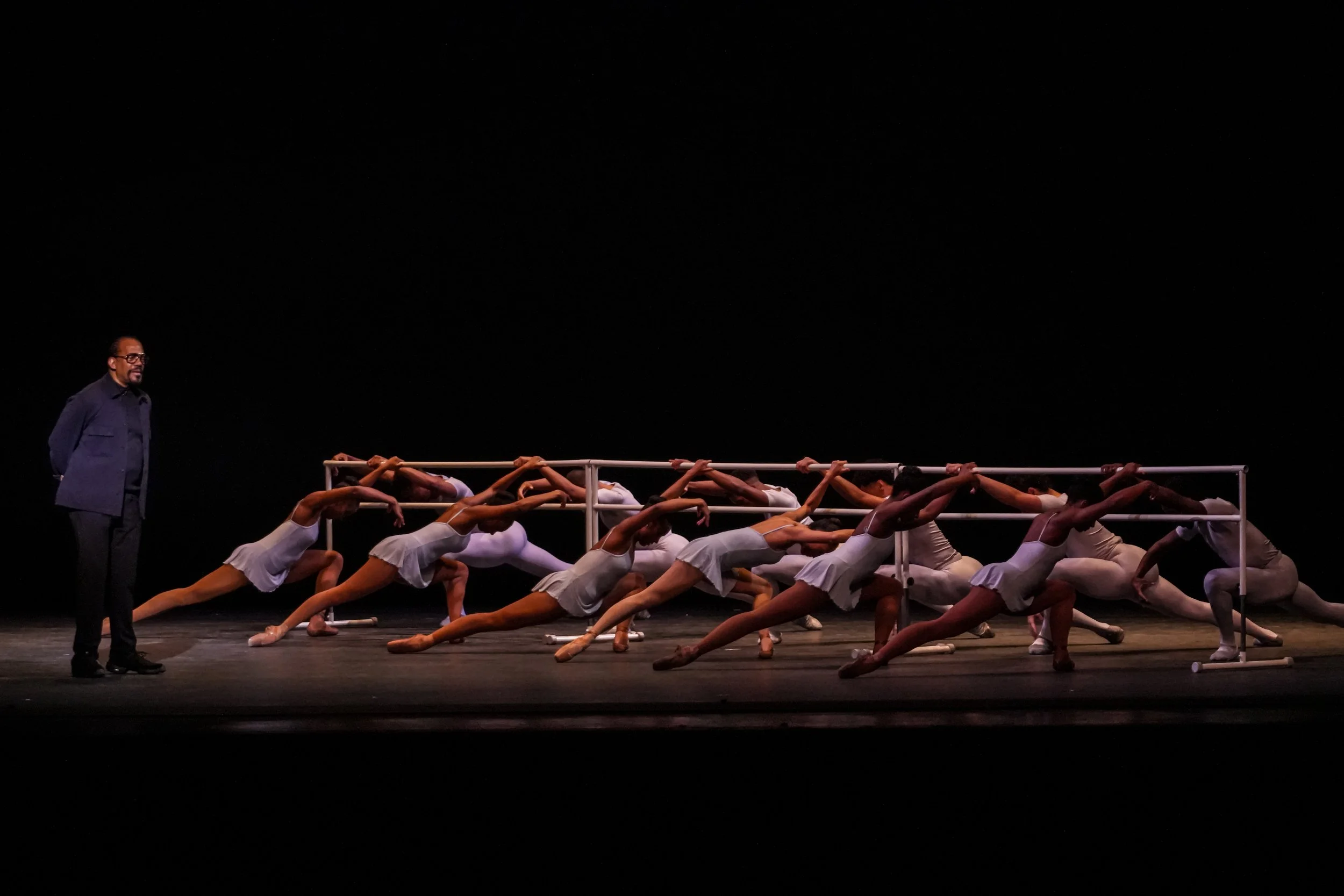

image by RACHEL PAPO

‘Firebird’ has such a rich artistic and cultural history. What does it mean to you personally to bring this legendary ballet back to life after more than 20 years?

Being that we are refocusing Geoffery’s work in general, it comes at the perfect time. Now that his painting career has been rediscovered, and we’re actively promoting it and exhibiting it, it comes just at the right time to be a continuation of his overall oeuvre. The fact is, as a painter first, everything else falls into place after. This is just one more aspect of the painter that couldn’t come at a better time. We’re re-exploring his work. Geoffrey has a gallery in NY and LA with James Fuentes and we just hosted his next exhibit in NYC, which opened in November at 52 White Street.

You’re working closely with the Geoffrey Holder Estate on this remount. What has the process been like honoring your father’s original vision while ensuring it resonates with modern audiences?

I am the estate. I am basically the representative of him on earth. To make it look as good as we can get it, one of our challenges is that both stagecraft and some other elements have changed. For example, ‘Firebird’ premiered over 40 years ago and those backdrops now are not usable. I had to digitally retouch all of the backdrops. And as such, a lot of work on my side is making sure that things look okay. We can’t paint the backdrops anymore, we have to print them. Some losses, some gains. Bottom line is, my job is making sure that at the end of the day, the piece looks coherent. These are issues Geoffrey didn’t have to deal with back then because everything was hand-done. I’m the closest thing to Geoffrey there is. Not by nature of being his son, but by knowing what his intent and process is. Notice I said that in the present tense. I wanted to be as close to Geoffrey as possible, so we hired one of his closest friends who supervised the painting of the original backdrop. When in doubt, I had him over my shoulder so I didn’t have to second-guess and ask myself “What would Geoffrey do here?” Between the two of us, we know what he would do. I went to the design shop to see the process and give them notes. I’m trying to keep it as organic as possible. Sometimes I have to “be” him. It’s a challenge because Geoffrey was a master at pulling focus. You ended up looking where he wanted you to look, and I’m trying to keep that up. There’s a lot to look at, but he knows how to pull focus.

Geoffrey Holder’s designs for ‘Firebird’ are iconic. How do you balance preservation with reinvention when reconstructing such detailed, imaginative worlds?

Going back to the source, we have to sometimes make compromises. For example, a lot of the fabrics that existed 40 years ago no longer exist. There’s always this compromise that we have to make and mostly for the better. Because the fabrics are better and more durable than they were 40 years ago. Sometimes we have to get the closest thing we can get to what it was. These dancers are a generation different from their predecessors, yet they’re the ones dancing in the costumes. I want to ensure these dancers can do the best they can with these costumes. Organza is organza, but there are different weights, different colors. I cannot be a total purist in any of this because I have to be as flexible as Geoffrey was. He worked with what he had. He worked like that not only as a designer, but as a choreographer. Dancers can be different so sometimes, and you’ll have to change a piece or part with a particular dancer in mind. We’re not restoring this to create a museum piece. 40 years later, we’re going to see a difference. For all intents and purposes, this is about now. We have to make them and this piece look as good as Geoffrey did 40 years ago. Being a purist doesn’t allow for flexibility. You have to have a little leeway. This isn’t just restoring a painting. There are other elements involved, there are lights, there are dancers, there’s an orchestra.

Your father’s artistry transcended disciplines—dance, design, theater, and film. How do you see that multidisciplinary legacy continuing to influence your own creative approach?

There’s a book of academic essays being written as we speak, and I’ve been asked to write the afterword. I recently came up with good first words as I met with his gallery. All of Geoffrey’s disciplines were extensions of his paintings. He practically painted every day of his life almost until the day he died. There was a work ethic there that, by DNA, I understand. My work is very different. I’m a little bit more on the technical end of things, having worked in film and television for 30 years, but we both have the same work ethic. The magic of Geoffrey is the fact that he was able to balance the abstract, and the literal, and he was able to balance the folk art and high art. He was a master at doing that. It’s a question of keeping that balance in check, the entire family has that. My mother has that, I have that, but Geoffrey was the source of all of that. He was the one who opened our eyes to all of it, and I’m sure my mother would say the same thing. It’s why they understood each other. They’re both very similar in that respect. She’s always there, involved in his work, whether or not she was directly involved. She was his muse, there’s always an element of her.

Was there a particular memory or lesson from your father that guided you through this process?

Yes and no. When you live with somebody that long, you learn by example. He was a big child in a big playground. Anything he saw, or touched, he made something out of it. Sometimes he would be able to pull something out of nothing. He was the kind of person, if you give a flashlight, fabric and a stage the size of a dining room table, he would somehow create something out of that. If you gave him a piece of wood, or a canvas, or masonite, or paint that was around, he would create something out of that. He was a good example for a lot of other people. Here I am right now. I’m supervising the costumes, I’m supervising the sets, and at the same time I have to take meetings, I have to deal with organizing, or working on a gallery exhibit. This is the lifestyle he led for over 50-60 years, non-stop. Even when he was slowing down, he still had to do it. That was his reason to be. If anything impressed me, it was the energy level needed. I’m keeping up, but I’m doing a lot of heavy breathing while doing so. If there’s a family business, the model has already been set. With ‘Firebird’, I could’ve said “Yeah, that’s fine, let’s do whatever.” But, if I see something and it doesn't work, I say “That’s not him. It’s not quite the aesthetic.” I have to reiterate how flexible he was based on whatever elements the times gave him. If I learned anything, it was how to be flexible. As long as at the end of the day it looks like it was his intent. We may have to make some alterations when we tech it, but at the end of the day, he’s on the stage. That’s why there’s a tendency to talk about him in the present tense, he’s present in his work. He’s been gone 11 years, but he’s still present in his work. I’ve had friends of his visit the storage space with his work and ask “Is he here? I smell him.” The smell of turpentine and vetiver cologne.

What are some of the most striking discoveries or challenges you encountered while revisiting ‘Firebird’s’ original materials and designs?

The fact that in looking at the original materials like videos, they held up better than I thought. Since he just designed this and didn’t choreograph it, I was a bit more removed. I’ve maybe seen this 3-4 times in my life, 30 years or so ago. Even then, there was this vision, and as a vision it works. Some things patina well, some things not so well. I’m trying to make sure this patinas well with respect to the compromises we’ve had to make along the way. I was lucky because he saved everything. When we first opened up his archive, besides it being a treasure chest of knowledge, it was like a fountain springing for the first time. He didn’t write a diary, he put a diary together with what he kept. He left a great blueprint. I guess where I become relevant in all of this is I’ve become 2.0, and my job as 2.0 is to somehow make all of this relevant to the people on stage dancing to it, and those who weren’t around 40 years to originally see it.

image by RACHEL PAPO

How does ‘Firebird’s’ Caribbean-inspired setting reshape the traditional ballet narrative, and what does that say about representation in classical dance?

I’m not sure it does, frankly. It’s still a ballet, and the purpose of Dance Theatre of Harlem was, in part, to prove that Black dancers had range. The fact of the matter is Mr. Mitchell had to prove that Black dancers could work in other idioms other than “Black dance.” His art doesn’t just register with a Black audience, rather an international audience. Geoffrey was international-minded in his art. I know the roots of many of his works before he even came to the US.

Working alongside Robert Garland and the DTH company, what has been most inspiring about collaborating with this generation of dancers?

Frankly seeing it continue. The dancers now are very different from the ones in the company 40 years ago. It’s nice to revere those who came before us, but also celebrate the strengths of those who are with us now. Working with dancers today, it’s important for them to have the context they need to pull it off. In as much, we have a caliber of dancers in this company that is top-notch. But, they’re doing pieces that existed before they were born. All they need is the right context. Physically speaking, they are technically more adept because the human body has evolved. Sometimes all they need to connect the dots is the right context, but that’s what makes this whole experience both challenging and rewarding.

‘Firebird’ is ultimately a story about freedom and transformation. How do you interpret that message for audiences in 2026?

People are going to come and see what they’re going to see, whether or not they are actively thinking what they’re seeing is transformational. They'll see something that will hopefully float them out of the theater. I’m not sure that the average audience member will think that technically or intellectually about it. I guess whatever the transformation is, it happens within the audience. If there is a 7-year old black girl in the audience seeing a bunch of black ballerinas, and decides she wants to become one, that’s your transformation. The audience is a participant in all of this whether they think so or not. Part of Geoffrey’s job in this is ensuring the child in the audience gets a chance to see something that inspires them to go “I want to do that” or “That is where I belong.” That was part of Geoffrey’s ethic, always.

How important is it for you to maintain the dialogue between heritage and innovation in re-staging works like this?

To have the correct balance. To understand the heritage enough to be able to transmit it to an audience that doesn’t have the context. We’ve been repped by a gallery for about 4 years. After Geoffrey’s 60s, he wasn’t repped by any particular gallery. Now that we have a gallery and scheduled exhibits in NY and LA, an interesting thing has happened. His artwork responds amazingly well with artists under 30-40 years old. I had this discussion with a curator and she said something that had not hit me until she said it. With Geoffrey being a polymath, and a good one at that, he’s registering with a generation of artists who grew up thinking polymathically. You have hip hop artists branching out to acting, there’s this cross referencing with other disciplines. He’s registering with a younger generation of artists and it’s magnificent. He was very much ahead of his time. In his 20s and 30s, I see so much of him or his nature in artists now who are at that age. Even aesthetically, the way he dressed the way he commanded himself.

As someone who straddles the line between preserving legacy and forging new creative paths, how do you define artistic stewardship today?

I’m still inspired by Geoffrey’s community because there was a massive support network. That symbiotic relationship between artists resonates just the same today. I’ll say Geoffrey had a knowledge of art and art history that was second to none. His book collection alone took me at least 3 years to really dive into. A good portion of that collection became the basis of the Institute of the Black Imagination. Dario Kalmese has a space Downtown NYC and he took over 1.000 of Geoffrey’s books to use as a foundation. There was so much of it and not just art. Spirituality, design, art on film, dance, you name it and some extremely rare. His collaborators truly inspired him, especially Josephine Baker. She deeply inspired Geoffrey, and his brother, Boscoe. Somehow they all just understood the message of giving back, and mentorship and being generous.

If your father could see this remount of ‘Firebird’ now, what do you think he would say?

Hopefully, he’d say I got it right. Hopefully he’d say “Good” and move on from there. There are enough people on this team who worked with him firsthand that as long as he’s on stage when people see it, I think we’ve done fine.

IN CONVERSATION WITH ROBERT GARLAND

Robert Garland, Artistic Director of Dance Theatre of Harlem, is ushering in one of the most anticipated seasons in the company’s storied history. With the 2026 New York City Center season, Garland curates a powerful program that bridges past and present, including the long-awaited revival of ‘Firebird’, last performed over two decades ago. Known for his distinct blend of classical technique and contemporary rhythm, he has been pivotal in carrying forward DTH’s mission to expand representation in ballet and connect diverse audiences through the transformative power of dance. As ‘Firebird’ takes flight again, Robert’s vision underscores DTH’s legacy as both a cultural institution and an ever-evolving creative force.

image by RACHEL PAPO

This upcoming season feels like a milestone for Dance Theatre of Harlem. What inspired the decision to bring ‘Firebird’ back after more than 20 years?

Until now, the newly revitalized Dance Theatre of Harlem has thrived by presenting fresh works and reimagining classic ballets. Yet, we felt the absence of a legacy piece, one with historical significance and cultural impact. We needed a production that could advance both ballet tradition and the Black cultural narrative. Stravinsky’s ‘Firebird’, as staged by Dance Theatre of Harlem, fulfills that need, bridging both worlds with power and purpose.

‘Firebird’ has such a special place in DTH’s history. What do you think makes this ballet timeless and relevant to today’s audiences?

Timelessness speaks to history, relevance speaks to the present. These two ideas converge in Dance Theatre of Harlem’s production of ‘Firebird’. Its enduring power lies in its origins, born in 1910 during a golden age of artistic collaboration in Paris, where groundbreaking music, design, and choreography came together to shape ballet’s future.

Dance Theatre of Harlem honors that legacy while elevating it. Geoffrey Holder, the visionary behind the ballet’s scenic and costume design, infused the work with a bold aesthetic that, in hindsight, aligns with what we now recognize as Afrofuturism. This cultural movement blends science fiction, fantasy, and historical imagination to envision liberated futures for Black communities. Through Holder’s lens, ‘Firebird’ embodies Afrofuturism long before the term was coined, merging tradition, innovation, and cultural identity in a singular artistic statement.

You’ve called this season a “celebration of renewal and connection.” Can you expand on what that means for you artistically?

I deeply value our alumni, but I also cherish our current audience just as much. Reviving ‘Firebird’ offers a unique opportunity to connect our rich, celebrated history with the vibrant energy of today’s Dance Theatre of Harlem patrons and ballet enthusiasts. It’s a beautiful way to honor the past while embracing the future.

How did the collaboration with Leo Holder and the Geoffrey Holder Estate come about, and what has been most rewarding about that partnership?

Mr. Geoffrey Holder has been a vital artistic collaborator with Dance Theatre of Harlem since its earliest days. In fact, DTH holds more of his choreographic works than any other company, including the iconic ballet ‘Dougla’. Our revival of ‘Firebird’ is a natural extension of that legacy, an enduring testament to Holder’s visionary contributions and the company’s commitment to honoring its artistic heritage.

As Artistic Director, what excites you most about balancing DTH classics with bold, contemporary works in this new season?

What excites me most is witnessing the artistic growth and versatility of the dancers in our company. I believe Dance Theatre of Harlem offers something for everyone, works that resonate deeply with African American cultural heritage, pieces rooted in classical ballet tradition, and bold contemporary creations that point toward future possibilities. This range is what makes our company dynamic, inclusive, and forward-looking.

This season also includes choreography from William Forsythe and Jodie Gates. How do you curate a program that reflects both tradition and innovation?

William Forsythe, though American by birth, built much of his choreographic career in Europe, where his innovative approach to ballet gained international acclaim. Jodie Gates, whose roots trace back to her time as a ballerina with the Joffrey Ballet, brings a deep understanding of the American ballet tradition. Both choreographers embody a unique blend of past and future, grounded in the American aesthetic, yet forward-looking in their creative vision. Their contributions reflect a dynamic intersection of legacy and innovation.

image by AUSTIN RICHEY

DTH has always been about inclusion, access, and breaking boundaries. How do you see that mission evolving under your leadership?

I see our mission evolving through the continued growth of the Dance Theatre of Harlem School. It’s disheartening to witness fewer young Black children, and children of color more broadly, considering the arts, especially dance, as a viable path. Our school in Harlem plays a vital role in reversing that trend, now more than ever. It stands as a beacon of possibility, nurturing talent and inspiring the next generation to see themselves in the world of dance.

The partnership with the University of North Carolina School of the Arts is a fascinating addition. How did that collaboration shape the ‘Firebird’ revival?

Opportunity and access have always been cornerstones of Dance Theatre of Harlem’s mission, values shared by the University of North Carolina School of the Arts in its academic approach. From the talented dancers in their program to the music department’s generous contribution of a recording of Stravinsky’s ‘Firebird’, this collaboration has proven mutually enriching. It has benefited both our professional institution and their student body, creating a meaningful exchange of artistry and education.

You’ve been part of DTH for decades, first as a dancer, now as Artistic Director. How has your understanding of the company’s legacy evolved over time?

While I understand the question, I believe it deserves reframing. The real inquiry should be “How has the public’s perception of Dance Theatre of Harlem’s legacy evolved over time?” Years ago, Arthur Mitchell often heard that he had to choose between being a social service organization and a ballet company, a notion that deeply disheartened him. But Mitchell believed he could do both, uplift a community and create exceptional art. That belief remains at the heart of what we continue to do today.

What do you hope audiences take away from seeing ‘Firebird’ and the broader 2026 program?

Possibility. Arthur Mitchell once said “The arts ignite the mind, they give you the possibility to dream and to hope”. That sentiment continues to guide us. My hope is that people, especially young people, leave our performances inspired, with a renewed sense of imagination and belief in new possibilities.

DTH is known for mentoring young artists. What does nurturing the next generation of dancers mean to you personally?

Culture, and especially the arts, stands at the forefront of our shared humanity. These creative pursuits are essential to building a more empathetic and compassionate society. The arts possess a unique power to elevate the human condition in ways that surpass business, commerce, or even sports. They challenge us to feel, to reflect, and to imagine a better world.

Looking ahead, what’s next for DTH beyond this milestone season? Are there new directions or collaborations you’re excited to explore?

Absolutely. And there’s more to come. Stay tuned.